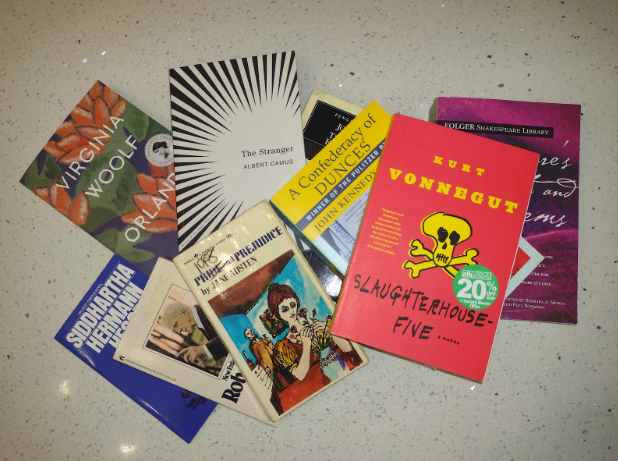

When I read the 1942 classic “The Stranger” by Albert Camus in seventh grade, I was amazed that literature could incite such beauty, thought and extreme worth.

My interest in literature began not in the classroom, but during my own independent reading because the English curriculum failed to reveal to my peers and I the aesthetic pleasure buried within the depths of classic and great literature.

This problem begins with not only how literature is taught in the early stages of education, but also in the ways teachers cram ideas into lessons to meet district demands.

In elementary school, where it all began, language arts assignments always took on a laborious tone. The primary goal of reading closer into a text was to complete graphic organizers identifying elements of narrative such as conflict, solution, theme, mood, etc.

As elementary schoolers have no keen interest in their schoolwork and would rather rush to play with friends, the ability to skim through work and identify its key elements as quickly as possible became the primary goal of reading in school.

Out of those elementary elements of fiction, one word always seemed particularly overlooked: mood. There was no goal to help students understand the emotion of what they read. Literature was not treated like an art that you’re supposed to feel, but something to use to pass a test.

In sixth grade, my class had the choice to read “Peter Pan,” “Treasure Island” or “Robinson Crusoe.” I chose to read “Peter Pan” because of its short length. However, I found myself interested in the reactions I saw to “Robinson Crusoe,” a 1719 book which was largely concerned with the religious developments of a man stranded on an island. It was the first work that my peers had read that was particularly complex and introspective.

Though, those who read “Robinson Crusoe” complained that nothing happened in the story. There was little focus on the introspection of Robinson at all. The book showed a life that was a bore, and with this brought up existential questions that probed for deeper meaning these kids were not prepared to analyze with the English skills they were taught. To them, literature wasn’t about the questions of life, emotional content, or aesthetics and maybe if it was it was focused on organizing these elements, not unpacking them and experiencing the book as a whole.

The book I saw my peers most enjoyed was “The Outsiders.”

However, I didn’t see any students cry at the emotional highs or think about where the questions were posed. They liked it because these elements were only supplementary to the content of “The Outsiders.” It lacked real questions, and its speedy plot skipped over the aesthetic or existential qualities of its setting to focus on larger-than-life fires and teen gang fights.

Literary history gets blown aside. Too often have I seen kids amazed by the literary timeline, with the belief that everything even the slightest bit archaic comes from the time of Shakespeare and that the time of Shakespeare was in ancient times, not in the early modern period.

It makes more sense when I look in my barely used English textbook, in which multiple units get ignored. Teachers, forced to teach things like rhetoric or the elements of fiction repeatedly, have no time to teach literature as an art.

Educators need to foster an appreciation of literature that focuses on the feelings and ideas of a text, not its components. There also needs to be a prioritization of challenging literature that engages ideas through connecting with people and not solely through an action-packed plot. Finally, schools should attempt to teach literature’s importance and how it connects to history.

It is vital to not look down upon everything that is old, pines for deeper meaning or invites the need to reread because doing so helps people better understand each other and the world around them. An appreciation for the way language can be used to create beautiful works makes people more self-aware of how they write and speak.

It is time to engage with literature aesthetically, for its own sake.