The world behind the signs

When the bell rings, the halls of Ocean Lakes spontaneously crowd with students rushing to their next class.

Most people chatter in English. Some catch up in Spanish. Others try practicing the new French, German or Japanese words they learned.

Yet in the midst of this hubbub of audio, a select few rapidly move their hands in intricate patterns: a closed fist, a straight finger, a wavelike motion and more. With their eyes focused and their faces expressing emotions, they communicate in this visual language without sound.

This is merely one example of the impact and depth of the deaf community at Ocean Lakes.

As the hub site for deaf and hard-of-hearing students in Virginia Beach, Ocean Lakes is extremely unique, housing interpreters, teachers of the deaf (TODs) and even American Sign Language (ASL) as a class.

However, it is astounding that hearing students and staff barely interact or communicate with members of the deaf community and vice versa. To bridge this gap, each side must gain a deeper understanding of the other’s day-to-day life, and that is the purpose of this article.

The interpreters at Ocean Lakes were all exposed to sign language in different ways.

“We were outdoors at a camp, and I saw a separate group of kids playing ‘red light, green light’ with signs,” interpreter Lisa Carbone said. “With my bachelor’s in theatre, I loved this, and I learned it really fast.”

Since ASL is an expressive language with clear cues on the face and upper body, such background definitely comes in handy.

Similarly, head interpreter Wendy Webster was introduced to ASL in adulthood; on the other hand, interpreter Marguerite Dugas began to learn ASL in middle school, inspired by her mother, who knew some ASL herself.

“I just really fell in love with it,” Dugas said. “I started self-studying and watched [many] YouTube videos.”

Though they all got started in different ways, their love for the language and passion for working with people led them to choose the path of interpreting. Unlike teaching ASL or simply learning the language, the journey of interpreting involves a diverse set of new skills and learnings.

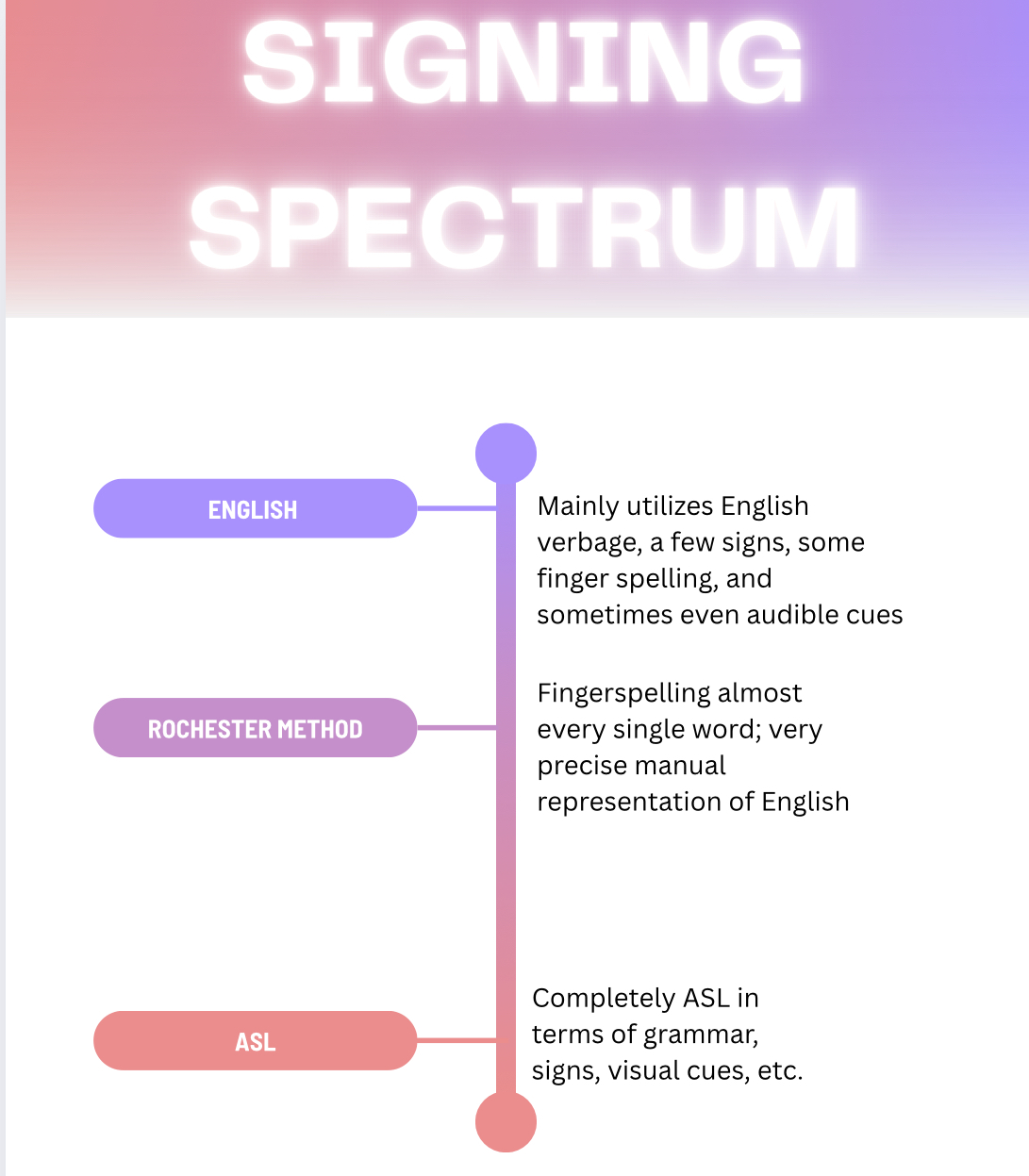

“There’s a spectrum of the way people sign,” Webster said. “It ranges from complete ASL to the Rochester method, where every word is fingerspelled. Somewhere in the middle is a combination of ASL and English.”

It is recommended that interpreters have a college education in not only ASL but also linguistics in general. Additionally, it is important to note that sign language is not universal. For example, as Webster found out during a mission trip to El Salvador, Deaf people from Spanish-speaking countries have their own sign language that doesn’t have many similarities to ASL as a whole.

In a school setting, interpreters move classes like students do and often shift between interpreting for different students. Some interpreters have an affinity for a certain subject; for example, some prefer interpreting the problems in math, while others feel stronger interpreting books in English class. Regardless, the interpreters often obtain the class notes and curriculum in advance to familiarize themselves with the specific jargon they might encounter.

Within interpreting, there are two different types: simultaneous and consecutive. Simultaneous interpreting involves listening and interpreting at the same time, whereas consecutive interpreters are delayed by a few seconds as they listen, comprehend and output the interpretation. There are advantages and disadvantages to both; simultaneous interpreting can be accurate but exhaustive, while consecutive interpreting takes less of a toll but can easily lag behind the conversation. As is evident, an interpreter’s job is difficult and multi-faceted, but many affirm the fact that the calling is rewarding.

“It’s changed me to recognize the gifts or talents I have that really make a difference to people, especially in the medical setting,” Carbone said.

Dugas agrees with this outlook.

“Interpreting looks an awful lot easier than it is, but it’s fun for me,” she said.

Since birth, ASL teacher Mary Collier has been profoundly deaf.

Out of seven people in her family, Collier is the only one who cannot hear. She’s never let that get in her way, though, as she signs ASL and writes English very well. This is her fourth year teaching, and in addition to Ocean Lakes, she teaches ASL and guides interpreters in the Interpreter Training Program (ITP) at Tidewater Community College (TCC).

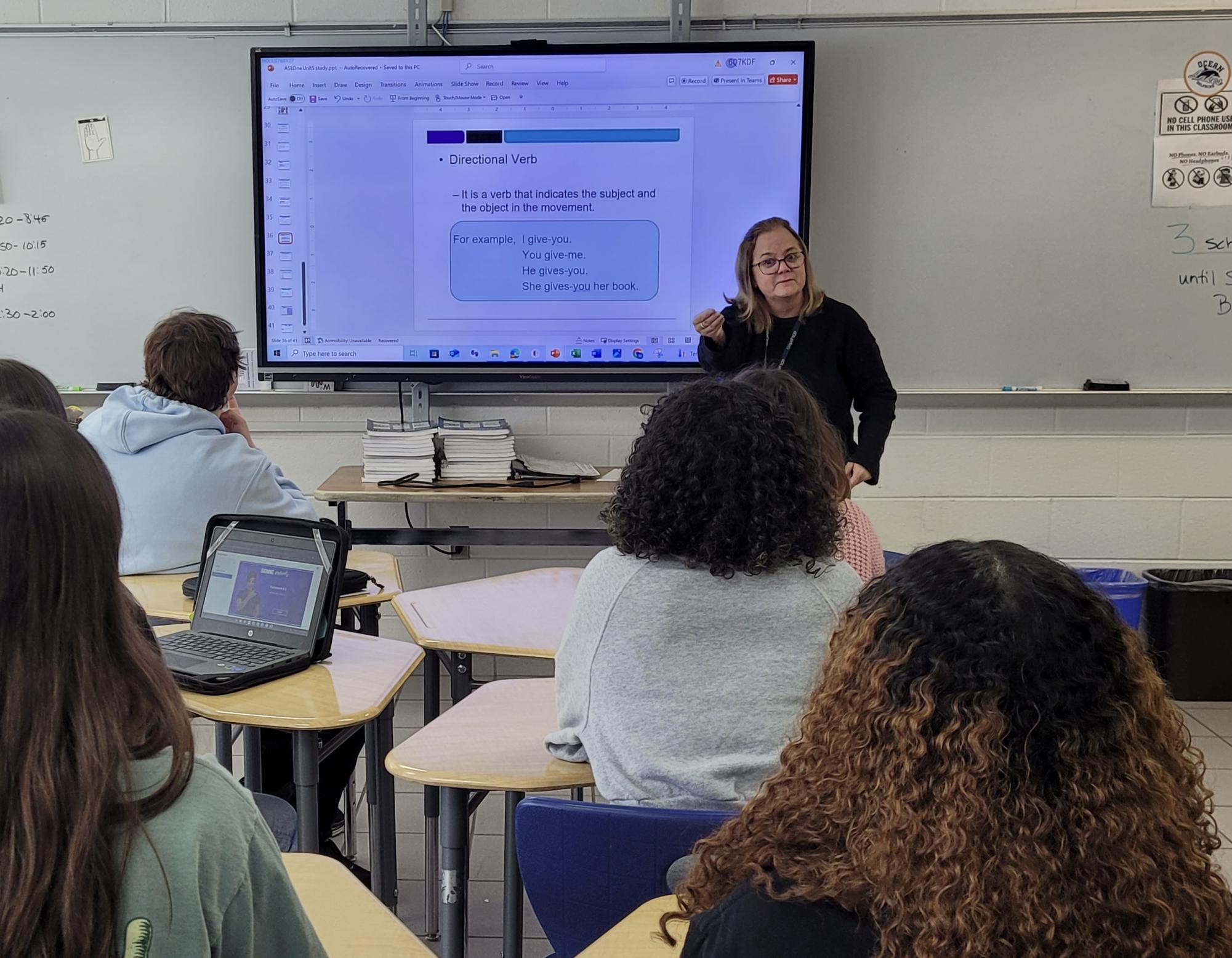

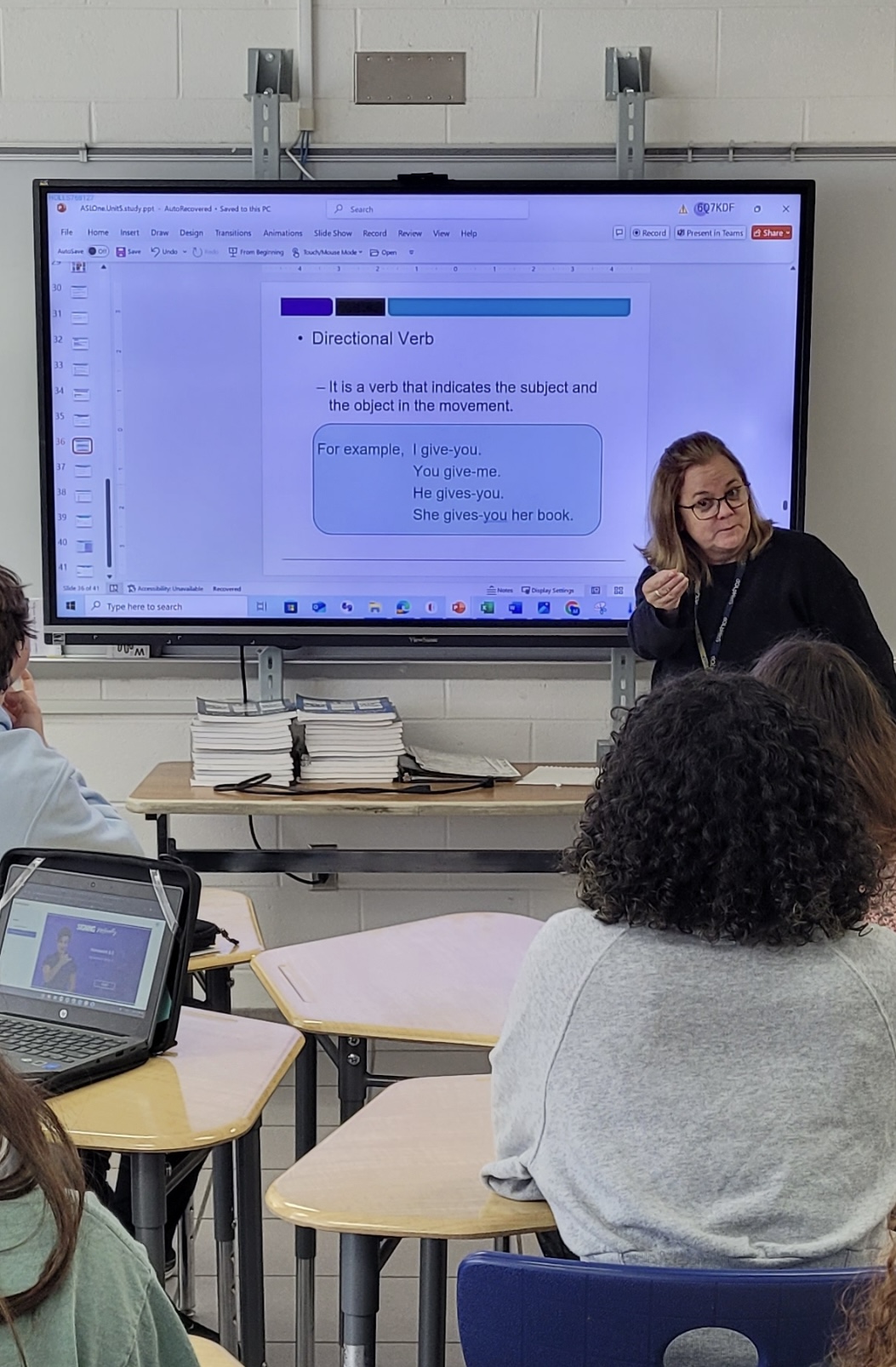

As a result, the learning environment in Collier’s classroom is very unique.

“I encourage the students to learn the language by full immersion,” she signed through an interpreter. “I make sure they have full eye contact; that’s how I teach.”

According to Collier, it’s difficult for students to “think” ASL because it has a completely different set of grammar rules as compared to English. Therefore, she usually utilizes English verbage to help students grasp the concept of ASL.

“The first four weeks are a huge challenge,” Collier signed. “The mind and hands, those two have to go together. A lot of the grammar is on the face; those are called non-manual signs.”

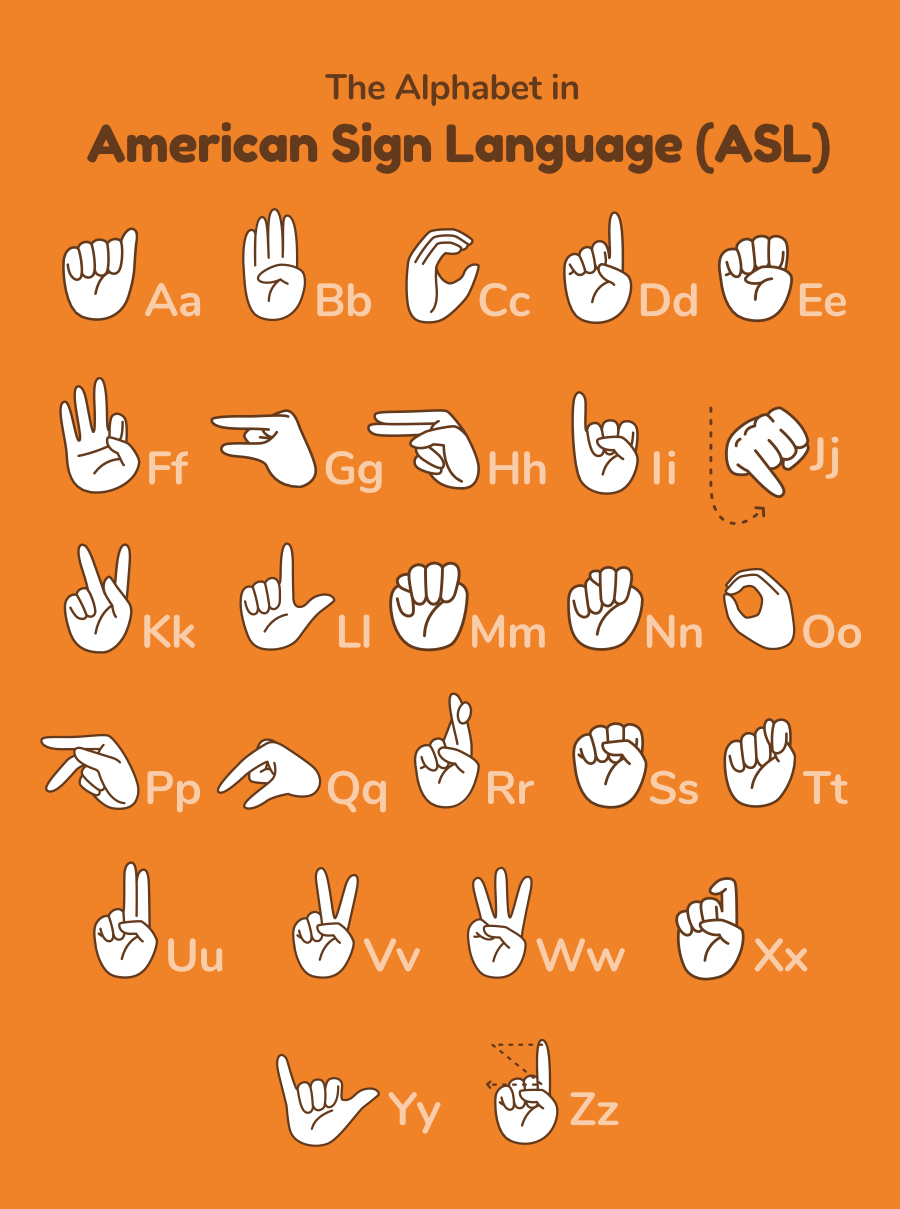

Non-manual signs are actually a large part of ASL. For example, showing “ch” or “oo” on the mouth indicates sizes; these are called mouth morphemes. Raising or furrowing the eyebrows and nodding the head can also be used to express certain ideas beyond just the manual signs.

For students interested in learning ASL or taking the class, Collier has a good piece of advice.

“Don’t be afraid to learn a new language,” she signed. “Be open.”

Agewise, Paul Miani is a junior, but he’s achieved so many credits that he’s ready to graduate this year with the class of 2025.

“I was born deaf, and this is my first year at OL,” he signed through an interpreter. “For two years I was at Princess Anne, and I would go to the Governor’s School for Visual Arts.”

Paul is the only deaf person in his family, so he learned ASL for the first time in a school setting. On the signing spectrum mentioned by Webster, Paul prefers to sign more ASL, though he uses some English elements in between. An important fact to note is that English is a second language for Deaf people; it doesn’t correlate directly to ASL. Therefore, there is a learning curve at the beginning.

His daily schedule this year consists of Government, both English 11 and 12, AP Precalculus, Economics, AP Computer Science and a block to work with a TOD. When asked about the pros and cons of “using” an interpreter, Paul was very positive.

“I don’t feel like I have any cons, but pros, I definitely have,” he signed. “I don’t feel isolated or alone; I just come to school and get my work done. I can’t nap during class though.”

Looking to the future, Paul will be attending the Rochester Institute of Technology, a university with an even mix of deaf and hearing students, to continue his studies. His experiences have certainly been unique as a deaf person, but he had a few pieces of pertinent advice for hearing students.

“I wish that more people cared to learn how to sign and knew that I’m a teenager like them,” Paul signed. “I have the same interests. Communicate better about the things we have in common; [after all], I just can’t hear.”

sheri Lussier • May 1, 2025 at 9:59 am

Thank you Mahi for writing so beautifully about this subject! You gave us a glimpse into what our remarkable ASL students think and feel in such a compassionate, yet informative way. It was nice to get to know them better, as well as their amazing interpreters and instructors. I really liked that you included the alphabet too! Thank you for the insight and thoughtful information. Fintastic job Mahi!

Sanjivani • Apr 17, 2025 at 10:27 pm

Superb Mahi. One more feather in your writers cap. What I like about is your selection of topic. People like to know and learn more about the deaf community and the interpreters. Very well written. It shows your empathy.

Nandini Sakharpe • Apr 17, 2025 at 10:12 am

What an insightful journey through the world of interpreters and ASL culture!